Understanding HPV In The Eyes: What You Should Know About Ocular HPV

It's almost natural to wonder about HPV, a virus many of us have heard about, and how it might affect different parts of our bodies. While discussions often center on its impact on certain areas, a question that sometimes comes up, you know, is about whether HPV can show up in the eyes. This can be a bit of a curious thought for many, and it's certainly worth exploring what we understand about this less common aspect of the human papillomavirus.

Basically, HPV, which stands for human papillomavirus, is a very common type of virus. My text tells us there are about 200 different kinds of HPV that have been found so far, and each kind tends to prefer infecting particular spots on the body. So, while some types might cause issues in one area, others might be more inclined to affect another. It's a rather diverse group of viruses, in a way.

When we talk about HPV, it's also pretty important to remember that it’s a virus, not a disease itself. It’s the human papillomavirus, to give its full name. This virus, you see, doesn't attack our blood, so it doesn't spread through blood. Instead, it mainly goes after the surface cells of our skin and the mucous membranes, which are those moist linings inside our bodies. We're going to explore what this means for the eyes, and if this virus can, in fact, make its way there.

Table of Contents

- What Exactly is HPV?

- How HPV Spreads

- The Immune System's Role and Persistent Infections

- Addressing the Question: HPV in the Eyes

- Why Understanding HPV Matters for Everyone

- Frequently Asked Questions About HPV and the Eyes

What Exactly is HPV?

So, when people talk about HPV, they are actually referring to the human papillomavirus. This virus is pretty widespread, and my text mentions that there are about 200 known types of it. That's a lot, you know, and each type has its own preferred places to infect. It's not like one type attacks everything; they are somewhat specialized in where they tend to cause issues. This distinction is actually quite important for understanding its effects.

The Many Faces of HPV: Types and Their Targets

My text tells us that with around 200 different types of HPV identified, it's clear this virus family is very diverse. Each of these types, in a way, has its own favorite spots on the body to infect. For instance, some types might be more commonly found in the genital area, while others might prefer the skin on your hands or feet. This is why you see different kinds of warts or lesions appearing in different places, depending on the HPV type involved. It's not a one-size-fits-all kind of situation, which is that interesting.

This variety in HPV types also means that the symptoms, or even the lack of symptoms, can differ quite a bit. Some types might cause visible growths, like warts, while others might cause no noticeable signs at all. It’s a bit like how different kinds of plants grow best in different environments; these virus types, they too have their preferred "environments" within the human body. So, knowing this helps us understand why HPV can manifest in so many ways, and why it's not always obvious if someone is carrying the virus.

High-Risk vs. Low-Risk: What's the Difference?

When you hear about HPV, you'll often hear terms like "high-risk HPV" and "low-risk HPV." My text explains that the main way we tell these apart is by how likely they are to cause cancer. Low-risk types, typically, cause things like common warts, which are usually not a big health concern, though they can be annoying. These types are less likely to lead to serious health issues, which is good to know.

On the other hand, high-risk HPV types are the ones that have a greater potential to cause cancer, especially if they stick around for a long time. My text points out that about 90% of cervical cancers, for instance, are caused by persistent infections with high-risk HPV types, like HPV 16 and 18. So, while HPV itself isn't a disease, the high-risk types, when they hang around, can definitely lead to more serious problems down the line. This distinction is really important for understanding the potential impact of an HPV infection.

HPV: A Virus, Not a Disease

It's important to be clear: HPV isn't a disease itself; it's a virus. My text emphasizes this point. It's the human papillomavirus, and it doesn't attack the blood. So, you won't find it spreading through blood transfusions or anything like that. Instead, its main targets are the surface cells of our skin and the flat, scale-like cells in our mucous membranes. These are the linings of areas like the mouth, throat, and genital tract, for example. That's where it typically sets up shop.

Because it targets these specific types of cells, the manifestations of HPV are usually seen on the surface. This means things like warts or changes in the skin or mucosal lining. It's not something that makes you feel generally sick, like a flu virus might. So, while it can lead to health problems, it doesn't cause a systemic illness throughout the body in the way some other viruses do. This distinction, you know, helps clarify what an HPV infection actually means for a person's health.

How HPV Spreads

Understanding how HPV moves from one person to another is pretty key, too. My text gives us some clear insights into the main ways this virus gets around. It's not just one way, which is something many people don't realize. Knowing these pathways can help us think about prevention, and just how common this virus actually is in the population. It's surprisingly widespread, after all.

Common Pathways: Sexual and Close Contact

My text makes it clear that sexual activity is the most significant way HPV spreads. The virus really likes to infect the reproductive system and other mucous membrane areas, so it makes sense that sexual contact is a primary route. This is why, you know, many HPV infections are often linked to sexual partners. It's a very direct way for the virus to move between people who are in close, intimate contact. This is actually why it's so common among sexually active individuals.

Beyond sexual activity, my text also mentions close contact as a way HPV can spread. This means skin-to-skin contact, even without sexual activity, can sometimes transmit the virus. For instance, if someone has a wart caused by HPV on their hand, and they touch another person's skin, there's a possibility of transmission. So, while sexual contact is the main one, it's not the only way the virus can get from one person to another. This is an important detail, too, to keep in mind.

Unexpected Ways: Environmental and Mother-to-Child

It's interesting to note that HPV can spread in ways that might not be immediately obvious. My text points out that environmental transmission is a possibility. For example, researchers have found HPV DNA in vaginal samples from teenage girls who haven't had sex. This suggests that the virus can be picked up from the environment, perhaps from contaminated surfaces, though this is less common than direct contact. It's a bit of a surprise for many, that.

Another way HPV can spread, my text suggests, is from mother to child. This is known as mother-to-child transmission. While not as frequent as sexual transmission, it means a baby could potentially pick up the virus from their mother during birth. So, it's not just about direct contact between adults; there are other pathways the virus can take, which, you know, broadens our understanding of how widespread HPV can be in different populations. These less common routes are still important to acknowledge.

Men as Carriers: An Important Role

My text highlights a really important point about men and HPV: even though there isn't a clear rule for men to get regular HPV checks, men can still carry the virus. This means they can be carriers of HPV, even if they don't show any symptoms themselves. And this, you know, has significant implications. If a man is carrying the virus, he can very easily pass it on to a woman.

When men transmit HPV to women, it can lead to persistent infections with certain high-risk types, like HPV 16 and 18. As my text explains, these persistent infections are strongly linked to precancerous changes and cervical cancer in women. So, while men might not experience the same serious health issues from HPV as women sometimes do, their role as carriers is pretty crucial for public health. It emphasizes that HPV is a shared concern, and not just something that affects one gender. This is, actually, a key piece of information.

The Immune System's Role and Persistent Infections

Our bodies have an amazing ability to fight off infections, and HPV is no exception. Most of the time, our immune system does a pretty good job. But sometimes, it doesn't quite manage to clear the virus, and that's when things can get a bit more complicated. Understanding this balance between our body's defenses and the virus is, you know, really important for seeing the bigger picture of HPV infection.

Clearing the Virus: What Usually Happens

It's actually quite reassuring to know that for many people, HPV infections are temporary. My text points out that studies show about 80% of women can clear the HPV virus on their own within two years of getting infected, even without any specific treatment. This is because our immune system is pretty good at recognizing and getting rid of the virus. So, for most people, an HPV infection is something their body handles naturally, which is a very positive aspect of the situation.

This natural clearance means that simply having HPV doesn't automatically lead to serious problems. It's a common infection, and for the vast majority, it comes and goes without much fuss. This fact, you know, helps put a lot of minds at ease, as the initial thought of having HPV can be quite concerning for some. It highlights the body's natural resilience against this widespread virus.

When HPV Lingers: The Risk of Ongoing Infection

While most people clear HPV on their own, my text also mentions that a smaller group of women can't get rid of the virus. When HPV stays in the body for a long time, we call it a persistent infection. And this, you see, is where the risk increases. Persistent infections, especially with high-risk HPV types, can lead to abnormal cell changes that might become cancerous over time. It's the ongoing presence of the virus that causes concern.

My text clearly states that persistent high-risk HPV infections are closely linked to precancerous lesions and cervical cancer. In fact, it says that 90% of cervical cancers are caused by these types of infections. So, while the body usually handles HPV well, it's those cases where the virus hangs around that need careful attention. This is why regular screenings and follow-ups are so important for detecting any changes early on, you know, before they become more serious issues.

Addressing the Question: HPV in the Eyes

Now, let's get to the heart of the matter for many readers: what about HPV and the eyes? While my text focuses on general HPV facts and its common sites of infection, it doesn't specifically detail HPV in the eyes. However, based on what we know about HPV's nature—that it attacks skin and mucous membranes—we can consider the possibilities. It's a question that, you know, often sparks curiosity because it's not the typical place people think of when they hear about HPV.

Is Ocular HPV Common?

Given the widespread nature of HPV, it's reasonable to wonder if it can affect areas like the eyes. The truth is, HPV in the eyes, often referred to as ocular HPV, is not nearly as common as HPV infections in other parts of the body, like the genital area or throat. It's a rather rare occurrence, in a way, and not something that doctors see every day. Most discussions about HPV focus on its more frequent manifestations, so this aspect tends to get less attention.

While it can happen, it's not a primary concern for the general population when thinking about HPV. The types of HPV that typically affect the eyes are usually low-risk types, which cause benign growths, rather than the high-risk types associated with cancers in other areas. So, while the possibility exists, it's not something to be overly worried about in the same way one might be about cervical HPV, for instance. This distinction, you know, helps put things into perspective.

How Might HPV Reach the Eyes?

Since HPV primarily spreads through direct contact with infected skin or mucous membranes, if it were to reach the eyes, it would likely happen through a similar mechanism. For instance, if someone has HPV on their hands, perhaps from touching an infected area, and then they touch their eyes, the virus could potentially be transferred. This is a form of self-transfer, or what's sometimes called autoinoculation. It's a bit like how a common cold virus can spread when you touch your face after touching a contaminated surface.

Another less common way, theoretically, could be through very close, intimate contact where the virus is directly transferred to the eye area, though this is not a well-documented or common route. The key thing is that HPV needs direct contact with a susceptible surface to establish an infection. So, while it's not the usual route of transmission, the eyes do have mucous membranes, which are, you know, a type of tissue that HPV can infect. This makes the possibility, albeit rare, something to consider.

What Could HPV in the Eyes Look Like?

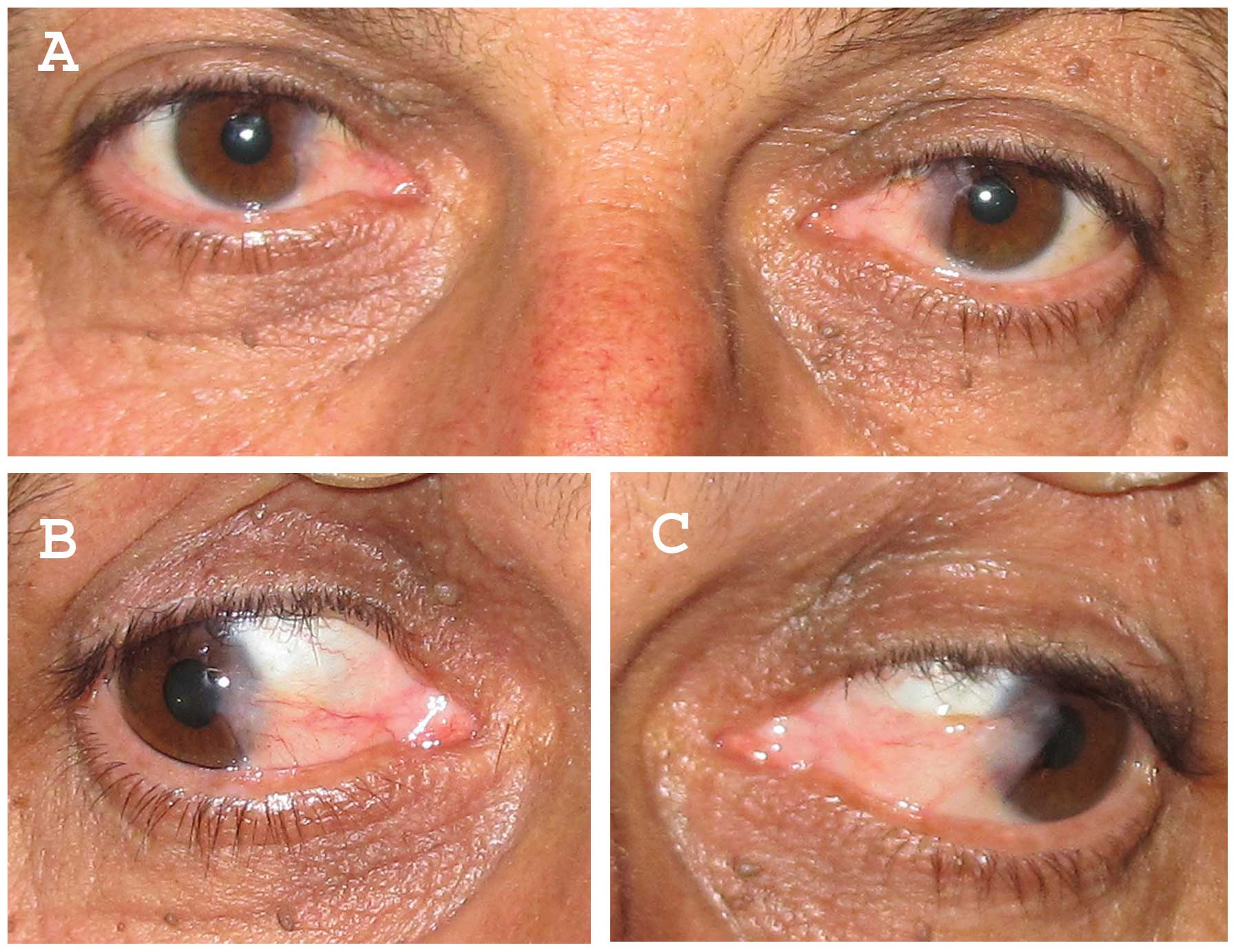

If HPV were to infect the eyes, the most common manifestation observed is usually a type of growth called a conjunctival papilloma. These are benign (non-cancerous) growths that appear on the conjunctiva, which is the clear membrane covering the white part of the eye and the inside of the eyelids. They might look like small, fleshy bumps or clusters, and they can vary in size. They are, you know, similar in appearance to warts that HPV causes on other parts of the body.

These growths are typically not painful, but they can sometimes cause irritation, redness, or a feeling like something is in the eye. In some rare cases, if they grow large enough, they might affect vision or cause discomfort. It's important to remember that these are usually caused by low-risk HPV types, meaning they are not typically associated with cancer. So, while seeing a growth on the eye can be alarming, it's generally a benign condition if it's HPV-related. This is, actually, a very important distinction to make.

Why Understanding HPV Matters for Everyone

Even though HPV in the eyes is not a common topic, understanding HPV in general is incredibly important for everyone. My text gives us a lot of reasons why this virus deserves our attention, going beyond just one specific area of the body. It's about knowing how to protect ourselves and those we care about, and recognizing the broader health implications of this widespread virus. This is, you know, a truly significant public health concern.

Beyond Cervical Cancer: A Broader Picture

When people hear about HPV, the first thing that often comes to mind is cervical cancer, and for good reason, as my text clearly links 90% of cervical cancers to high-risk HPV. However, it's important to remember that HPV can cause other health issues too, and affect other parts of the body, like the throat, anus, and even, in rare cases, the eyes. So, it's not just a concern for one specific type of cancer or one gender. It's a much broader picture.

My text also mentions that about 10 out of 80 women, or roughly 80% of women, get infected with HPV at some point, with genital HPV infections being very common. This shows just how widespread the virus is. So, while cervical cancer is a major concern, thinking about HPV means understanding its potential for various manifestations and its prevalence in the population. This broader awareness is, you know, pretty essential for everyone.

Prevention and Awareness

Knowing about HPV, its types, and how it spreads is a big step towards prevention. My text emphasizes that HPV infection is very common, and while most infections clear on their own, persistent infections can lead to serious health issues. This is why, you know, awareness is so vital. Understanding the main ways it spreads, like through sexual activity and close contact, can help people make informed choices about their health.

While there's no explicit mention of HPV vaccines in the provided text, general awareness about HPV often includes information on vaccination, which is a very effective way to prevent infection with the types of HPV that cause most cancers and warts. Regular screenings, like Pap tests for women, are also crucial for detecting any changes early on. So, staying informed and taking preventive steps are key to managing the impact of HPV on public health. This is, actually, a really proactive approach to health.

Learn more about HPV prevention on our site, and link to this page for more details on vaccination.

Frequently Asked Questions About HPV and the Eyes

Here are some common questions people often ask about HPV and its potential effects on the eyes, based on general understanding of the virus.

Can HPV cause eye problems?

Yes, while it's not common, HPV can cause growths, typically benign papillomas, on the conjunctiva of the eye. These are usually not serious but can cause irritation or affect vision if they get large. It's a rare occurrence, you know, but it is possible.

How common is HPV in the eyes?

Ocular HPV infections are considered rare compared to HPV infections in other parts of the body, like the genital area or throat. Most people who have HPV will not experience eye involvement. So, it's not something to be overly concerned about for the general population, which is, actually, a relief for many.

What are the symptoms of HPV in the eye?

If HPV affects the eye, the most common symptom is the appearance of a growth, often described as a fleshy, cauliflower-like bump, on the surface of the eye or inside the eyelid. These growths, called papillomas, are usually painless but might cause redness, irritation, or a feeling of something in the eye. They can also, you know, sometimes affect vision if they are in the way.

Will vaccination against human papillomavirus prevent eye disease? A

Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia and carcinoma: distinct clinical

Viral involvement in the pathogenesis and clinical features of